Towards a climate-neutral and inclusive transport system in Turkey

How the country on the Bosporus is boosting the share of electric cars

Preface

A blog post by Johanna Wietschel, Project Manager, Transport Economics, at Agora Verkehrswende

For Turkey to achieve its target of peaking emissions by 2038 at the latest and reaching net-zero by 2053, the transformation of the road transport sector is crucial (Republic of Türkiye, Updated First Nationally Determined Contribution, 2023). Road transport today accounts for approximately 20 per cent of the country’s CO₂ emissions, making it one of the biggest sources of climate-damaging greenhouse gases. The number of cars on the road has been increasing significantly for years – and if current trends continue, is expected to rise even further. At the same time, there is a high level of public awareness in Turkey for the importance of climate protection: 72 per cent of the population is concerned about climate change, and nine out of ten support a national net-zero target.

Turkey’s Climate Change Mitigation Strategy and Action Plan 2024–2030, which came into force at the beginning of 2024, sets out measures such as shifting freight and passenger traffic to rail and maritime transport; expanding public transit; improving vehicle efficiency; promoting low- and zero-emission vehicles; and integrating clean energy into transport systems.

In the area of private car use, Turkey has taken important first steps towards decarbonisation, including offering tax incentives for electric vehicles. However, given the climate damage caused by combustion engines and the urgent need to switch to climate-friendly electric vehicles, the introduction of pricing instruments in passenger road transport is also needed. As economic instability and inflation are already placing a heavy burden on households in Turkey, these policies should combine environmental effectiveness with social balance.

Turkish tax policy supports e-mobility

Recent increases in the number of registered vehicles – particularly in the category of privately owned cars – reflect both growing mobility demand and changing consumer behaviour in Turkey. The number of registered cars rose from about ten million in 2014 to almost 17 million in mid-2025 – a 70 per cent increase, despite population growth over the same period of just 10 per cent (Turkish Statistical Institute, 2025). In 2024, car ownership in Turkey stood at around 178 vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants – meaning roughly one in five people owns a car. Germany counted 580 cars per 1,000 inhabitants in 2024, while in the European Union as a whole, there are 574 cars per 1,000 inhabitants (Acea, 2024).

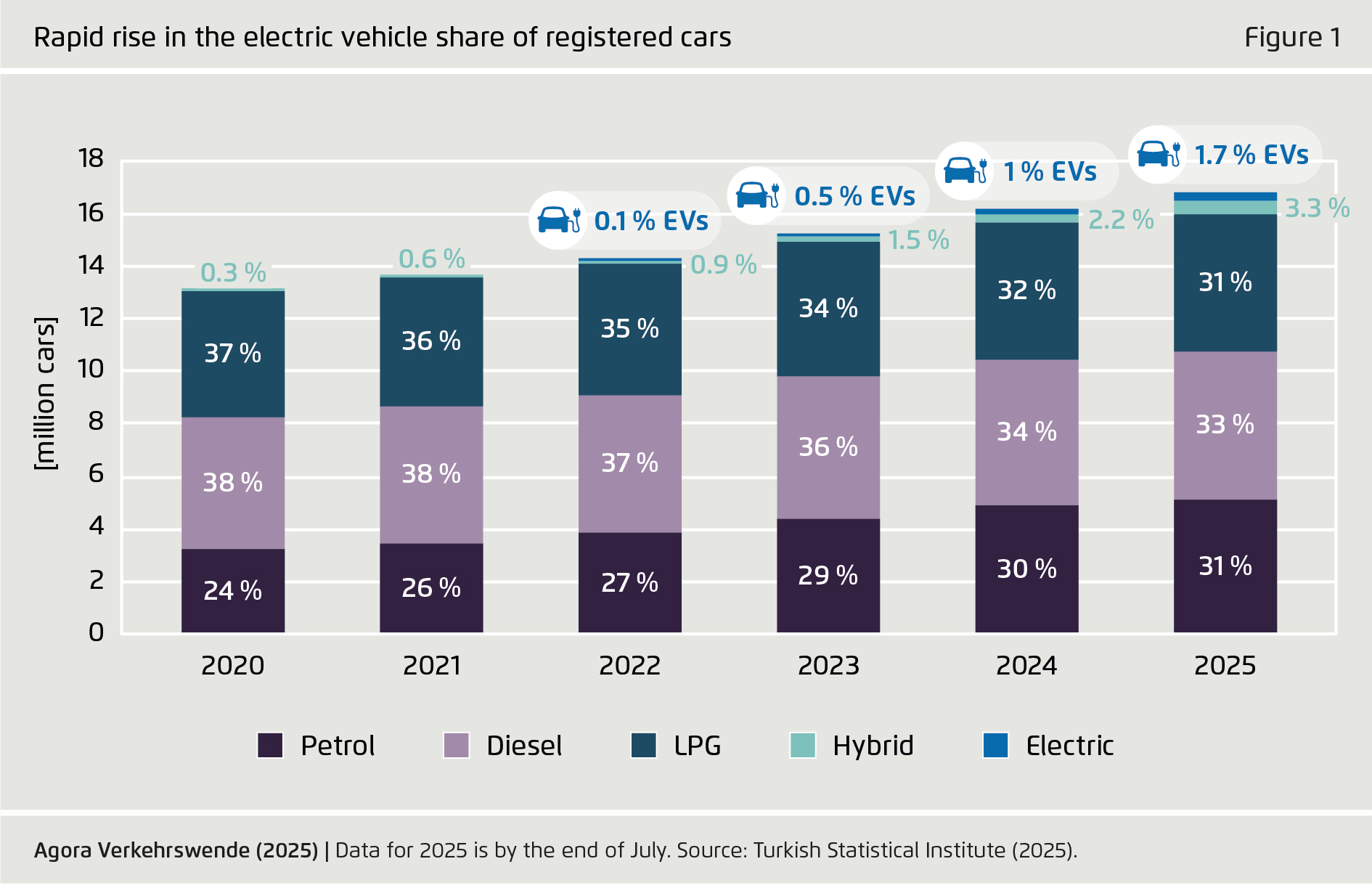

Notably, there has been a significant trend in recent years towards smaller cars and battery electric vehicles (BEVs): small-engine cars (up to 1,400 cubic centimetres) as a share of all registered cars rose from 40 per cent in 2020 to 50 per cent in 2024, while medium-engine cars declined from 55 to 35 per cent (Turkish Statistical Institute, 2025). Large-engine vehicles remained stable at around seven per cent. As of July 2025, BEVs made up 1.7 per cent (289,457) of all registered cars in Turkey – up from just 0.1 per cent in 2022 (see figure 1). This increase highlights the accelerating shift toward electric mobility. In the first seven months of 2025 alone, around 614,000 new cars were registered, with hybrids[1] and BEVs accounting for 27 and 17.2 per cent of the total, respectively. The share of BEVs in new passenger car registrations in Germany stood at around 18 per cent during this period.

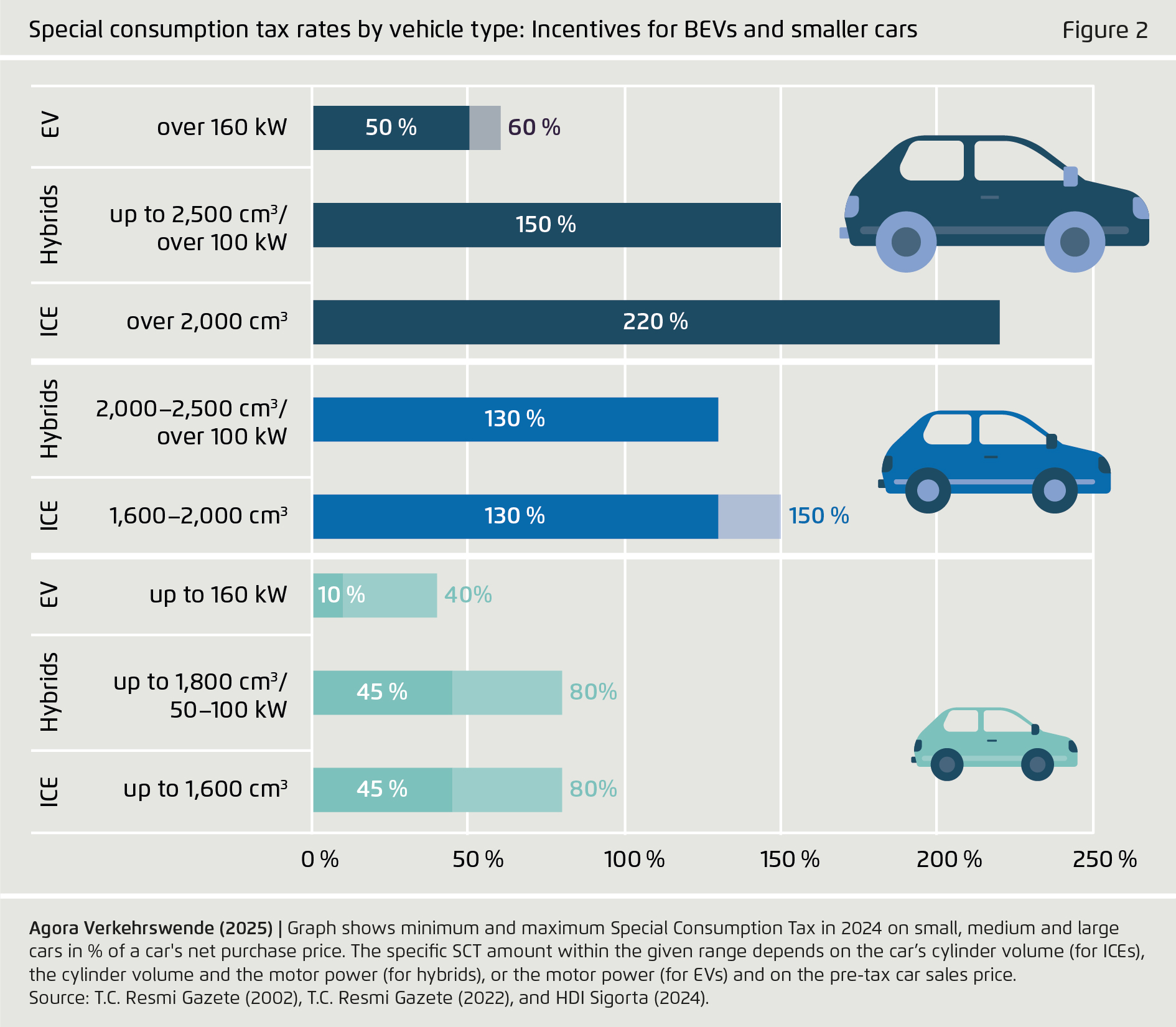

A key driver for these developments is Turkey’s tax system, which favours smaller cars and BEVs. The Special Consumption Tax (SCT) on small BEVs ranges from ten to 40 per cent of the net purchase price, compared to 45 to 80 per cent for equivalent internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles (see figure 2). For larger vehicles, tax rates on ICEs are as high as 220 per cent, nearly four times higher than the 50 to 60 per cent applied to BEVs.

Inflation and above-average transport expenditures are placing a particular strain on low-income households

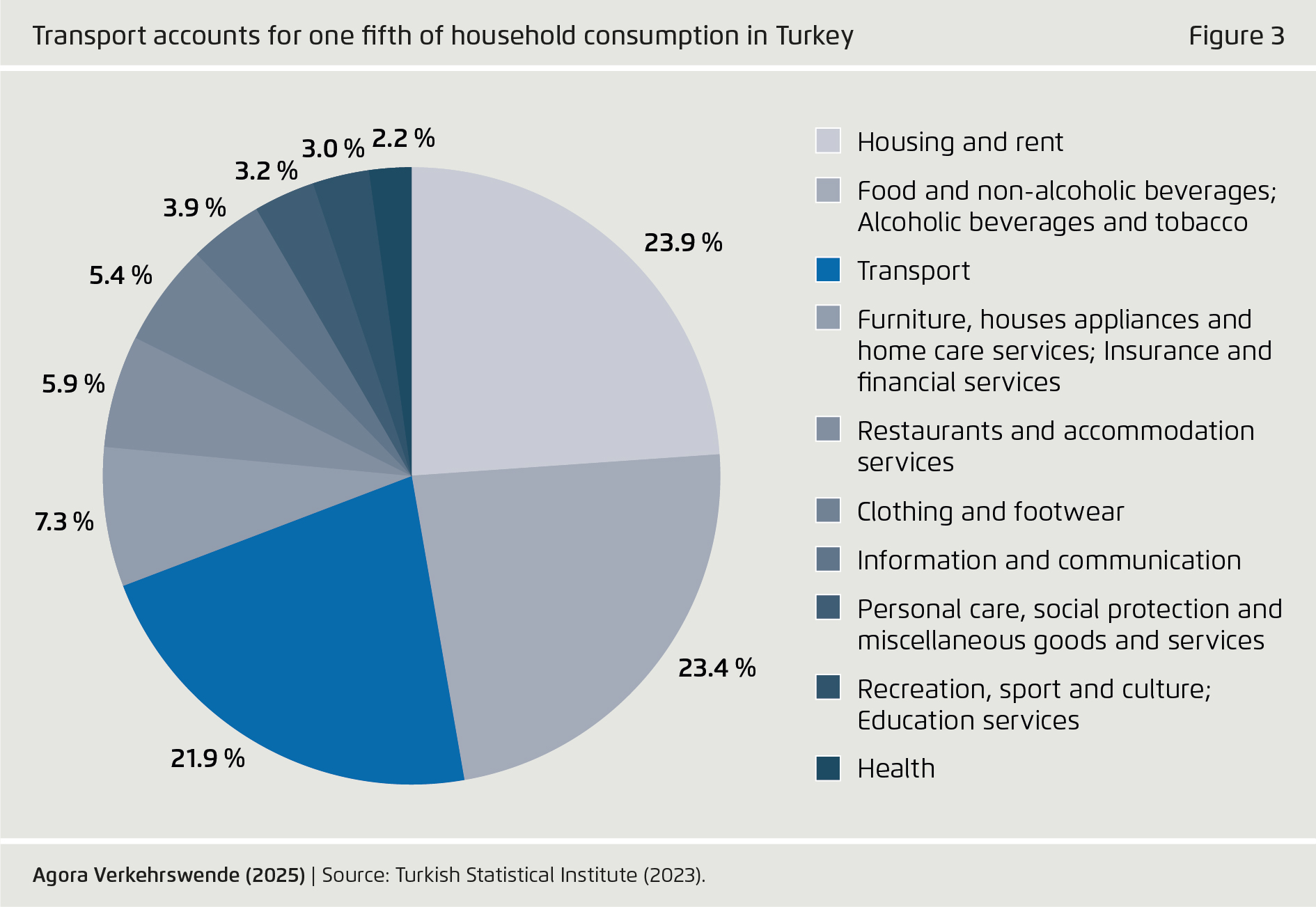

Turkey has suffered from high inflation in recent years, in part due to the weakness of the Turkish lira. Rising costs for goods, services, and energy have placed heavy burdens on low- and middle-income households, with ripple effects across society and the economy. Social participation is further impaired by the fact that mobility accounts for a higher share of household expenditures in Turkey than in other countries. In 2023, households in Turkey spent on average 22 per cent of their consumption expenditures on transport (see figure 3). By comparison, the EU average stood at just 13 per cent in 2023.

High-income groups allocate nearly one-third of their consumption spending to transport, demonstrating a pronounced willingness to pay for private vehicle use. While lower-income households tend to be more price sensitive and vulnerable to rising fuel costs, higher-income groups in Turkey demonstrate lower price sensitivity and a greater willingness to pay for transport. This means that high-income households in Turkey are not very responsive to price changes. Accordingly, even if fuel prices or car-related expenses increase, these households are still likely to continue driving.

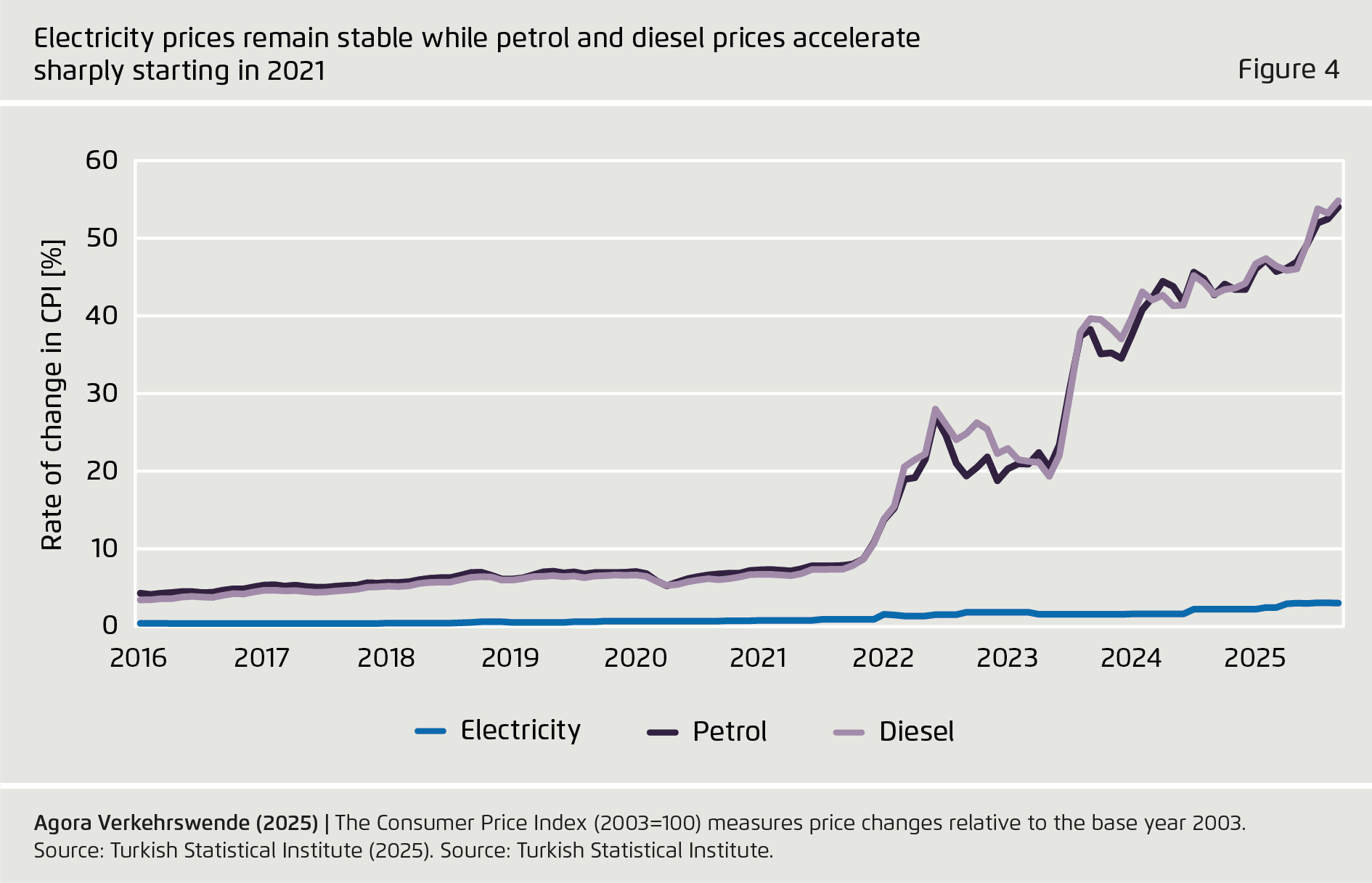

Figure 4 shows the annual rate of change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for electricity, petrol, and diesel. Electricity prices have remained stable at around two to three per cent throughout this period. Petrol and diesel prices show a sharp acceleration starting in 2021, reaching annual inflation rates of 45–55 per cent by 2025. This strong divergence between electricity and fuel prices provides a compelling economic incentive for consumers to switch to electric vehicles, helping to explain the strong market growth observed in Turkey's electric vehicle sector during this period.

An emissions trading system is planned – but does not yet include transport

Like many other countries, Turkey lacks a carbon pricing mechanism that fully reflects the true cost of CO₂ emissions. This creates a significant gap between the price consumers are required to pay for emissions and the true scope of the climate damage these emissions cause. Closing this gap could incentivise sustainability and support the broader transformation of the transport sector. By raising the price of fossil fuels, carbon pricing encourages cleaner alternatives and helps to align economic incentives with climate goals.

One option to establish a CO2 price is through an Emissions Trading System (ETS). Emissions Trading Systems set a cap on total emissions and allow companies to buy and sell emission allowances, thereby creating a market price for carbon. Turkey is preparing to launch a national ETS that covers emission intensive sectors like power generation, steel, and chemicals, with a pilot phase starting next year and full implementation planned for 2027–2034 (International Carbon Action Partnership, 2025). While the Turkish ETS is designed to drive cleaner industrial technologies and accelerate the shift towards renewable energy, the current plans do not yet cover the transport sector. This is a clear point of weakness, because conventional passenger vehicles are a major contributor to national CO₂ emissions. Turkish legislators should therefore consider the extension of a socially balanced ETS to road transport as part of long-term policy design.

With car ownership rising rapidly in Turkey, accelerating the shift to electric vehicles is crucial. By 2030, over 25 million passenger cars are expected on Turkish roads, of which 44 per cent will need to be plug-in hybrid or battery-electric to meet national decarbonisation targets. With plug-in hybrid and battery-electric vehicles representing just three per cent of the total vehicle fleet in 2024, there is thus significant work to do (SHURA Energy Transition Center, 2024). While the government has already adopted targets for the electrification of public fleets, similar goals are also needed for private vehicle registration.

Ensuring equity in climate and transport policies

Climate measures such as carbon pricing and fleet targets for electrification are essential for decarbonisation. Yet policy action should be designed to reduce rather than exacerbate social inequality – for example, by prioritising financial support for low- and middle-income households, or by directing investment into clean and reliable public transport, particularly in underserved areas.

Non-financial factors such as convenience, time savings, and infrastructure quality often play a larger role than financial incentives when it comes to high-income groups. Effective measures for encouraging the adoption of climate friendly mobility among high-income groups include: investing in reliable public transport, ensuring safe and convenient infrastructure for walking and cycling, and providing integrated mobility services that reduce dependence on car ownership.

To pursue socially just climate policy, policymakers need reliable, long-term data on transport demand, mobility behaviour, and associated expenditures, broken down by income, region, and other social factors. Data on travel behaviour should include modes of transport, travel frequency and distances, vehicle ownership, purposes of travel, and total transport-related expenditures. Granular data of this nature allow for socially balanced carbon pricing schemes, inclusive transport infrastructure planning, and evidence-based support programmes.

The decarbonisation of Turkey’s transport sector represents a crucial element of the country’s climate strategy. But the transition to clean mobility is not only about new technologies or carbon pricing – it’s also about people. By placing equity at the heart of climate policy, Turkey can ensure that its path to net zero is not only effective, but also inclusive.

An extended version of this article first appeared in August 2025 as an IPC-Mercator Policy Brief. The author, Johanna Wietschel, conducted research on Turkey’s transport transition as a Mercator-IPC Fellow in the 2024/25 cohort at the Istanbul Policy Center. Please note that the figures in the blog have been updated to reflect today’s data compared to the original version.

[1] The Turkish Statistical Institute lists hybrid vehicles as a separate category, without further differentiation between hybrid types (mild hybrid electric vehicle, hybrid electric vehicle, or plug-in hybrid electric vehicle).

Literature

Acea (2024): Motorisation rates in the EU, by country and vehicle type. Available at: https://www.acea.auto/figure/motorisation-rates-in-the-eu-by-country-and-vehicle-type/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

Agora Verkehrswende (2025): EV market development. Available at: https://www.agora-verkehrswende.org/publications/ev-market-development. Last accessed on: 28 October 2025.

HDI Sigorta (2024): Araç ÖTV ve KDV Hesaplama. Available at: https://www.hdisigorta.com.tr/hesaplayicilar/otv-kdv-hesaplama. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

International Carbon Action Partnership (2025): Turkish Emission Trading System. Available at: icapcarbonaction.com/en/ets/turkish-emission-trading-system. Last accessed on: 28 October 2025.

Republic of Türkiye (2023): Updated First Nationally Determined Contribution. Available at: unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2023-04/T%C3%9CRK%C4%B0YE_UPDATED%201st%20NDC_EN.pdf. Last accessed on: 28 October 2025.

Republic of Türkiye (2024): Climate Change Mitigation Strategy and Action Plan 2024-2030. Available at: https://iklim.gov.tr/db/turkce/icerikler/files/CLIMATE%20CHANGE%20MITIGATION%20STRATEGY%20AND%20ACTION%20PLAN%20_EN(1).pdf. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

SHURA Energy Transition Center (2024): Transportation Sector Transformation: Integrating Electric Vehicles into Türkiye’s Distribution Grids. Available at: https://shura.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Transportation-Sector-Transformation_Integrating-Electric-Vehicles-into-Turkiyes-Distribution-Grids.pdf. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

T.C. Resmi Gazete (2002): Özel Tüketim Vergisi Kanunu. T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Mevzuat Bilgi Sistemi, June 12, 2002, no. 24783. Available at: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?Mevzuat-No=4760&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

T.C. Resmi Gazete (2022): Cumhurbaşkanı Kararı -Özel Tüketim Vergisi Kanunu. T.C. Cumhur-başkanlığı Mevzuat Bilgi Sistemi, November 21, 2022, no. 32023/6417. Available at: https://www.re-smigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2022/11/20221124-2.pdf. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

Turkish Statistical Institute (2023): Household consumption expenditures. Available at: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Household-Consumption-Expenditures-2023-53801&dil=2. Last accessed on: 28 January 2025.

Turkish Statistical Institute (2025): Consumer Price Index. Available at: data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index. Last accessed on: 30 October 2025.

Turkish Statistical Institute (2025): Road Motor Vehicles. Available at: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Road-Motor-Vehicles-July-2025-54043. Last accessed on: 18 September 2025.