-

What are NDCs?

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are national climate action plans that form a central element of the Paris Agreement. They outline a country’s targets and actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate impacts, with the collective goal of limiting global temperature rise to well below 2°C while pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C by the end of this century.

The NDC process operates on a five-year submission and updating cycle. While earlier NDCs often laid out actions with a long-term view, many culminating in 2030 targets, the third round, due in 2025, is the first one to uniformly outline national climate actions with a specific and common implementation horizon through 2035.

This round represents a pivotal juncture, not just because it comes a decade after the Paris Agreement’s adoption, but because the window to limit global warming to 1.5°C is rapidly closing. The actions taken between 2025 and 2035 will be decisive in determining whether the world can meet this goal. Consequently, the level of ambition in these NDCs is a direct test of countries’ commitment to turning political promises into tangible emission reductions. The updated plans are intended to outline increasingly ambitious action and they coincide with the phase-out date for the sale of new combustion cars in several jurisdictions.

This cycle is also the first one to be informed by the Global Stocktake (GST), a comprehensive assessment of collective progress. The first GST process, which concluded in 2023, was based on commitments submitted in the run-up to COP26 in 2021. This stocktake underscored the significant gap between existing pledges and what is required to meet the Paris goals, adding further weight to the imperative for enhanced ambition in this round.

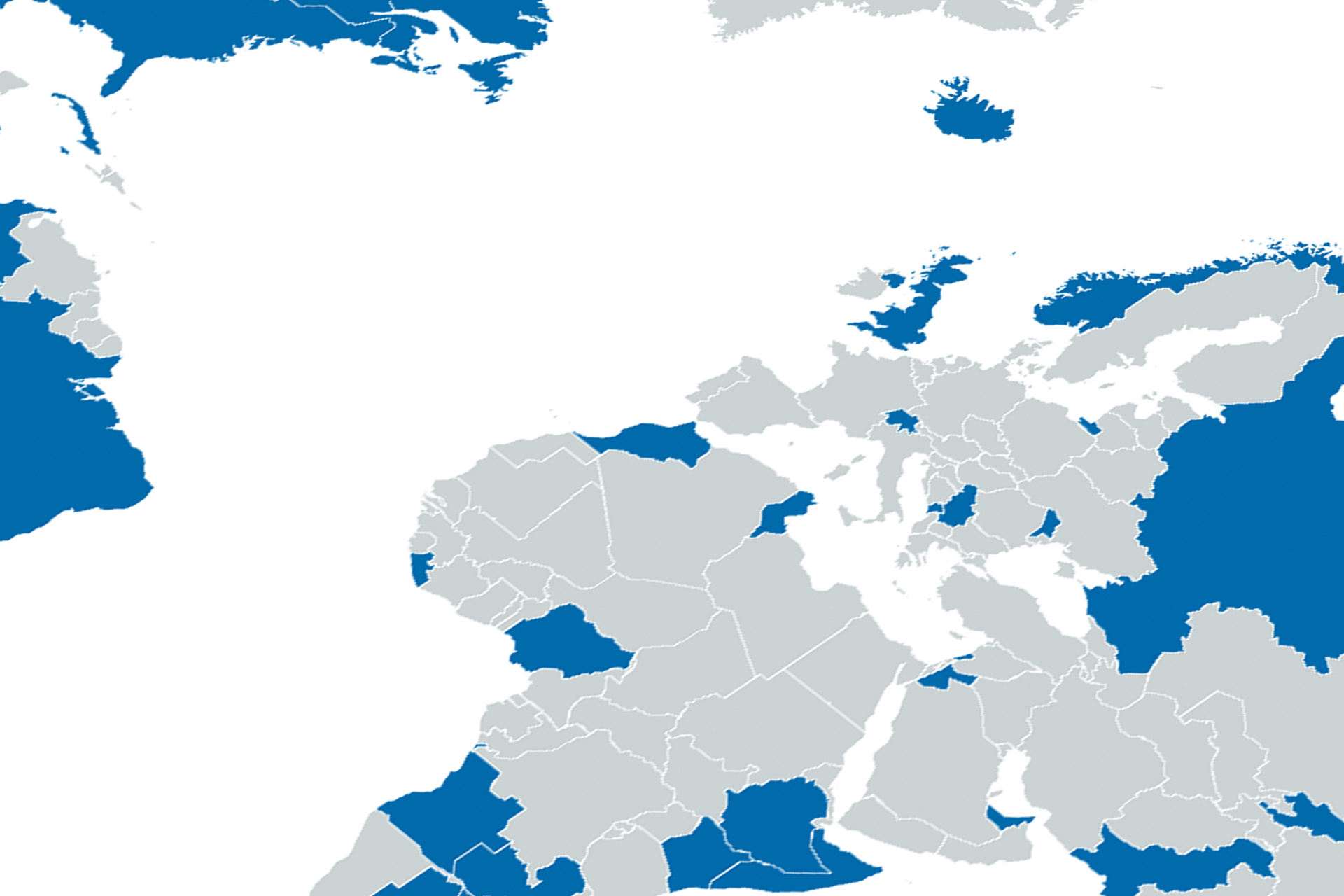

EV NDC World Map

Interactive map of global ambition to adopt electric vehicles (EVs) based on the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of Paris Agreement signatories

Data current to 15 December 2025

The EV NDC World Map

The EV NDC World Map illustrates the global ambition to adopt electric vehicles (EVs) according to the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted by countries under the Paris Agreement. The current edition of the map is based on the NDCs submitted up to 15 December 2025, drawing from the data contained in the NDC Transport Tracker maintained by GIZ and SLOCAT (2025) (v. 4.0).

Our aim is to provide a targeted overview of electric mobility in land transport, assessing the level of ambition in the field internationally while also identifying gaps in policy instruments and measures. This analysis seeks to provide input to both the electric mobility and climate communities, addressing shared priorities in addition to industry concerns.

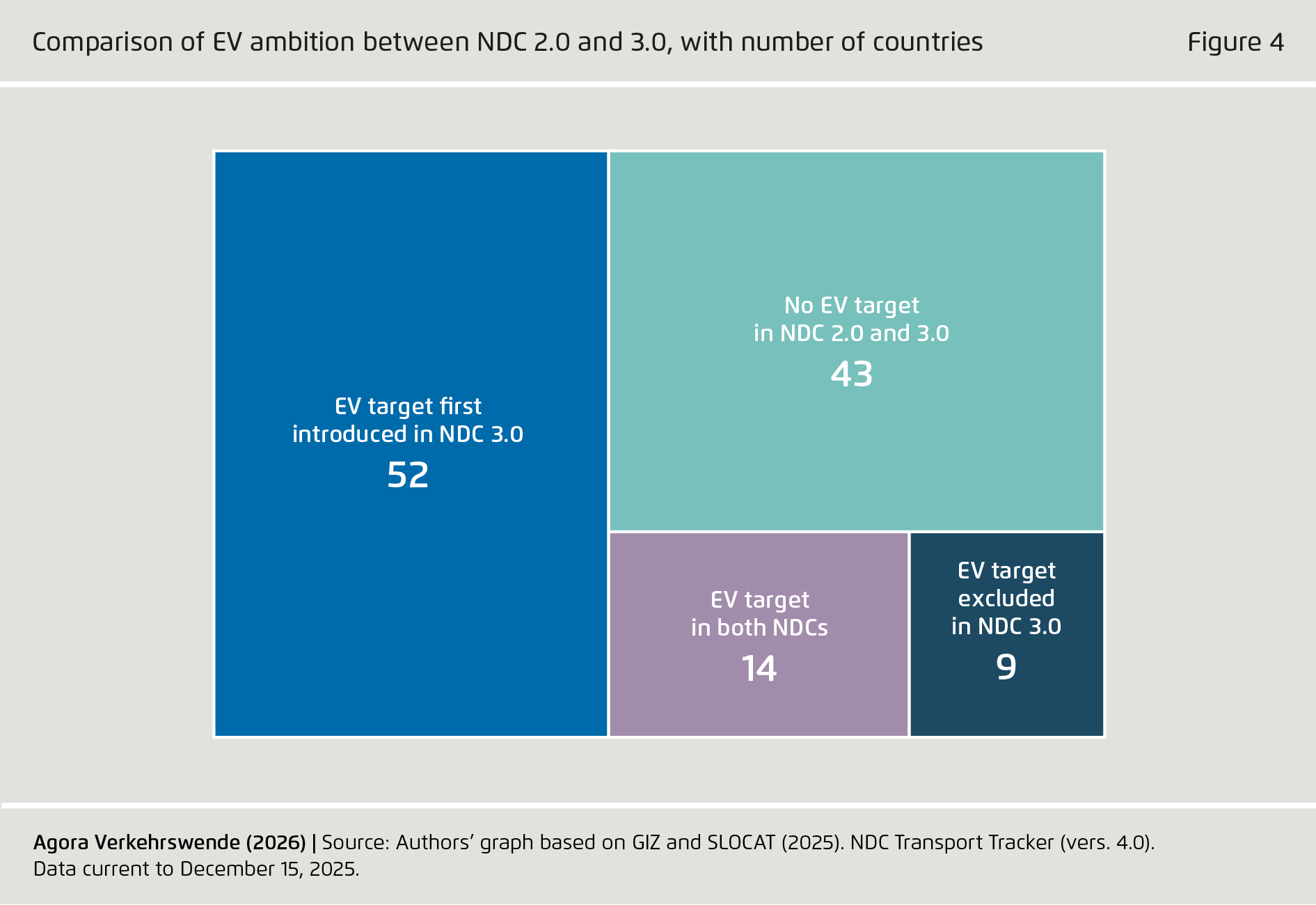

As of December 15, 128 countries (101 countries + 27 EU Member States) had submitted their third NDC.[1] Among them, 66 countries (52%) include specific electric mobility targets. This represents a significant increase of ambition, with 52 countries introducing electric mobility goals for the first time, compared to their previous submissions. Our assessment shows a high number of small and developing nations among the NDC 3.0 submissions that contain EV targets.

It is important to note that our analysis is based exclusively on the information contained within the submitted third-generation NDCs. Many countries have additional national strategies, targets, and measures detailed in dedicated policy documents, legislation, and national plans that may not be fully captured in their NDCs. Consequently, this review provides a specific window onto the commitments formalised within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process, which may not represent the entirety of a country’s national e-mobility landscape.

What are NDCs?

Why focus on electric mobility in transport?

-

Why focus on electric mobility in transport?

The transport sector represents a critical dimension of the global effort to mitigate climate change. As a primary contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, it accounts for nearly one-quarter of global energy-related CO₂ emissions, with road transport responsible for approximately 75 percent of that share. This significant emissions footprint underscores the urgent need for decarbonisation strategies that can deliver substantial and timely reductions.

Electric mobility stands out as a pivotal near-term strategy to achieve this goal. The International Transport Forum’s (ITF) Transport Outlook 2023 report identifies accelerated action on clean vehicles and fuels as the most impactful lever for decarbonisation. Indeed, this lever accounts for three-quarters of the emission reductions between the ITF’s Current Ambition and High Ambition scenarios.

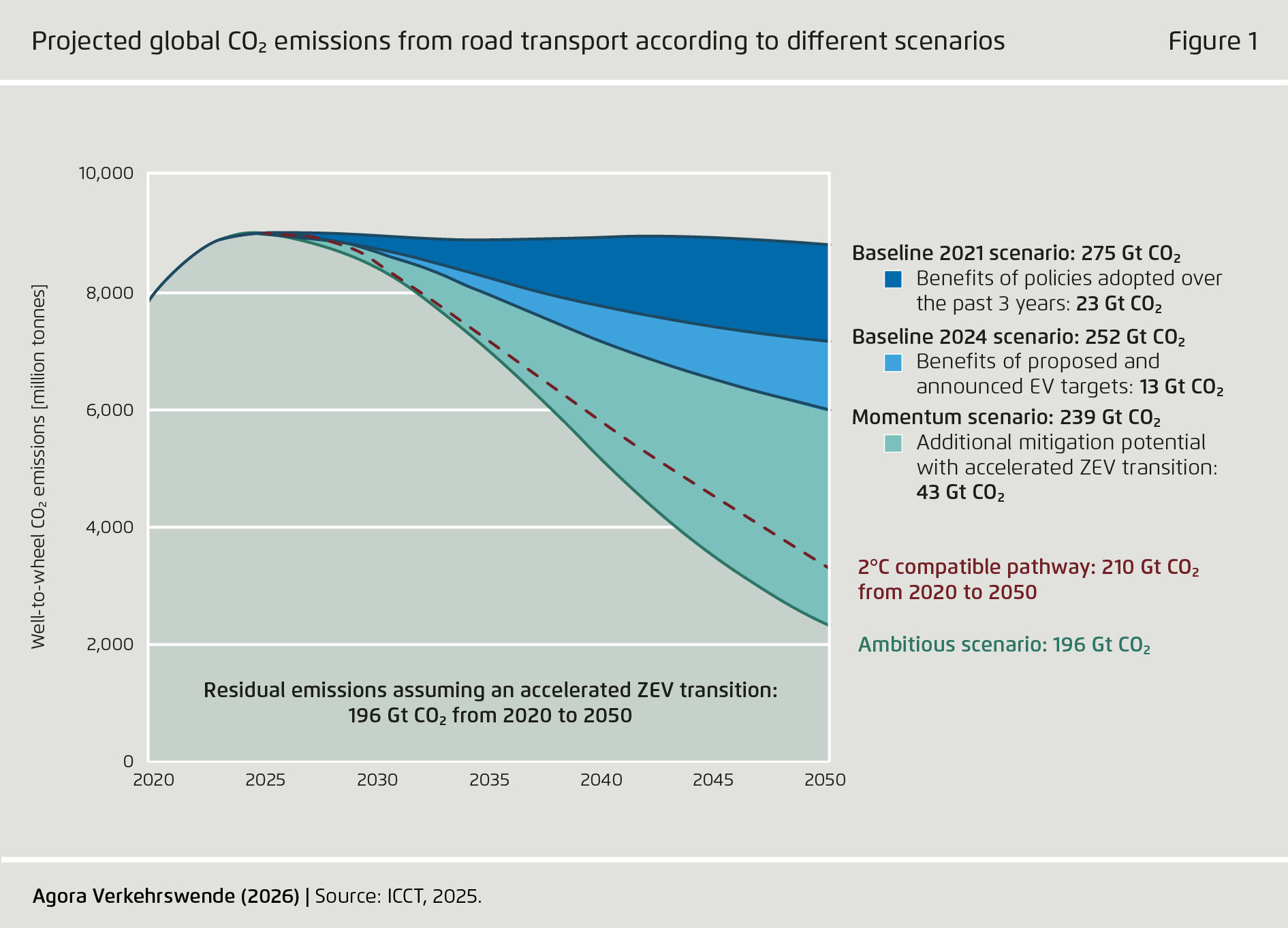

Recent analysis from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) confirms that the transition to e-mobility is not just a theoretical potential, but is already underway, driven by concrete policy action. The ICCT’s Vision 2050 report shows that policies adopted in major economies over the past few years have significantly improved the emissions outlook, putting global road transport CO₂ emissions on track to peak as early as 2025.

However, this positive momentum should not be taken as grounds for complacency. The same ICCT study serves as a crucial reminder that a significant gap remains between current policy commitments and a trajectory that is aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement (see Figure 1). Thus, while progress is real, it is not yet sufficient. There is a critical need to not only maintain but drastically accelerate the ambition to adopt electric mobility in national climate plans, including in the latest NDC round.

Findings on NDC 3.0 submissions

-

Findings on NDC 3.0 submissions

As of mid-December 2025, 128 countries had submitted their third NDCs, including the European Union, whose NDC sets the course for its 27 Member States.

According to our analysis, 66 countries (52%) include specific electric mobility targets in their NDC 3.0. This represents a significant increase in formal ambition, as 52 countries have introduced electric mobility goals for the first time (compared to prior submissions). Situating this policy ambition within the broader market, countries with NDC-based electric mobility goals now account for more than 62 percent of global car sales.[1] A broader view shows that 104 countries have incorporated some form of EV-related policies or measures, highlighting that while many governments are prioritising the sector, some of them are still lacking the inclusion of concrete, measurable targets.

The push for electric mobility encompasses major markets such as the European Union and China. The regulatory direction for the automotive industry is thus increasingly clear, despite the varying specificity of underlying commitments.

The list of parties with EV targets consists of: Angola, Azerbaijan, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Cambodia, Canada, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Côte d'Ivoire, Cuba, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Lesotho, Liberia, Mauritania, Mauritius, Moldova, Monaco, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Rwanda, Saint Lucia, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Suriname, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Vanuatu, Zambia, and the European Union.

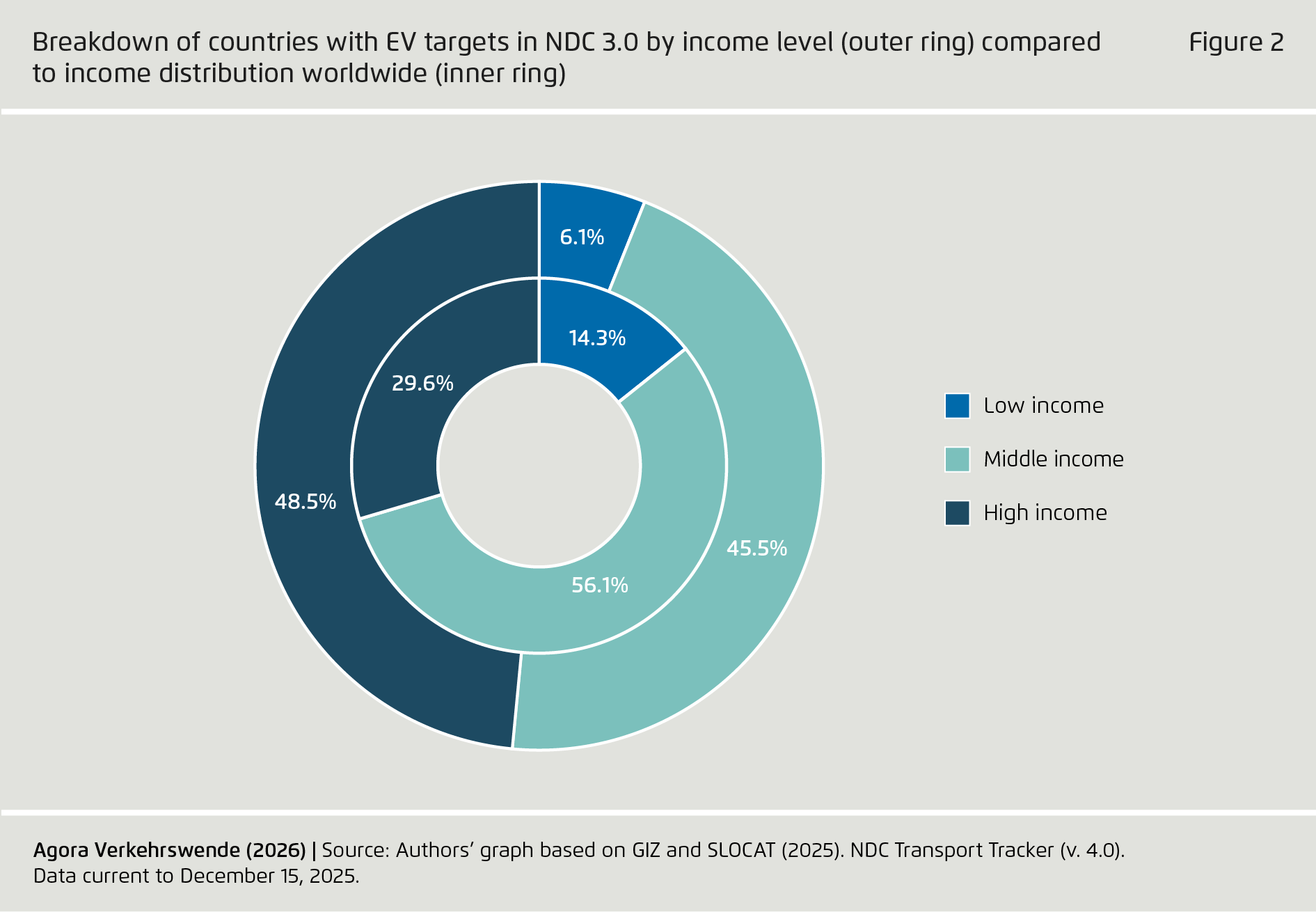

When examining the income-level distribution of countries with EV targets (see Figure 2), high-income nations represent about 48 percent of all countries with EV targets in their NDC 3.0, although they account for roughly 30 percent of all countries globally. This distribution is shaped by the structure of the UNFCCC submissions: the 27 member states of the European Union, which have mostly a high-income level, are represented by a single NDC, which intrinsically contains an EV target for all of them. The majority of the remaining commitments come from middle-income countries, which constitute about 46 percent of all countries with an EV target. This high rate of participation underscores that for developing countries and emerging economies, the NDC process is a crucial platform for signalling climate priorities and accessing international support.

Despite the political commitment to e-mobility that continues to gain steam among a diverse set of nations, the aggregate climate impact of these commitments remains limited. To date, countries with electric mobility targets in their NDC 3.0 account for just 34 percent of global transport sector GHG emissions. Among the top ten global emitters from the transport sector, Canada, China, and the European Union have incorporated a clear EV target in their latest submission. Major emitters such as the United States, Russia, and Brazil have thus far omitted such targets, and India has yet to submit its NDC 3.0.

Our analysis thus reveals two parallel stories in global climate action. First, ambition must expand beyond its current core: high-income leaders like the EU must be joined by other major emitters in formalising clear EV transition targets within their NDCs. Second, the burgeoning commitment from the Global South, evidenced by its high share of NDC submissions and EV targets, must be met with scaled-up international support. This is crucial for bridging the capacity gap, thereby ensuring their growing ambition translates into on-the-ground decarbonisation.

-

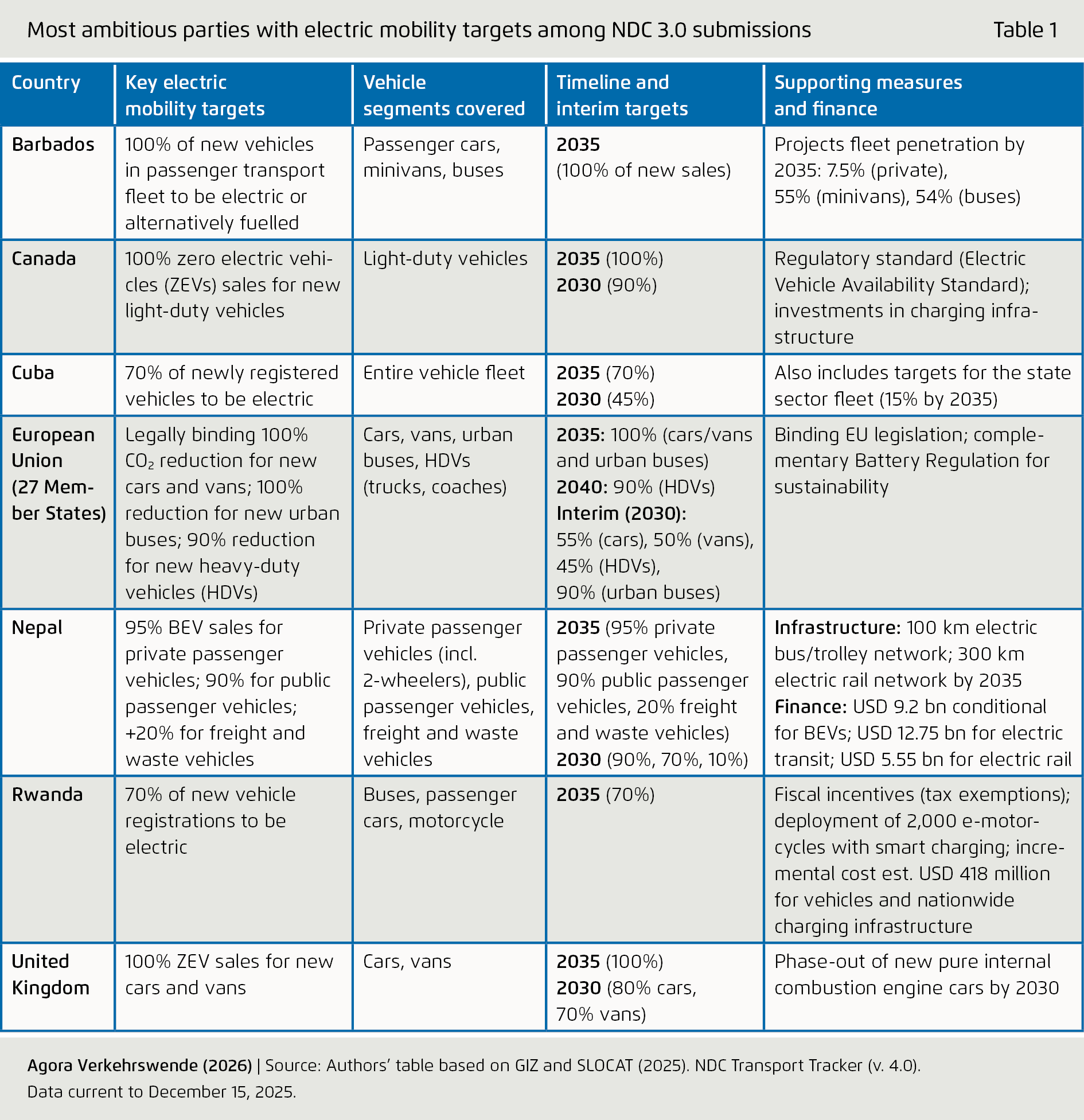

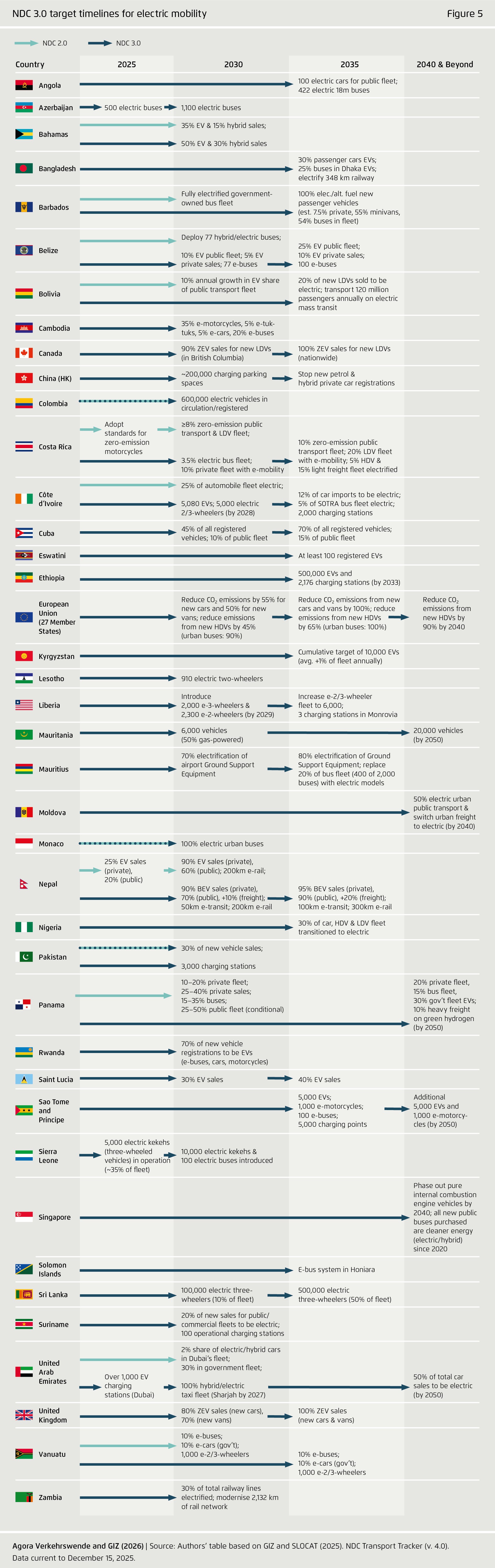

The most ambitious countries

Among the 66 countries with specific EV targets, some nations stand out by presenting not just percentage targets for electric vehicle (EV) sales, but also broad vehicle-segment coverage. In addition, they show a commitment to complementary infrastructure and industrial policies, and have undertaken detailed financial planning. The next table shows seven nations with particularly strong electric mobility ambitions among NDC 3.0 submissions.

The standout commitments from Canada and the United Kingdom are their legislated phase-outs of new internal combustion engine vehicles, providing regulatory framework for a 100 percent zero-emission vehicles (ZEV) market by 2035. However, it must be noted that both governments have recently modified implementation in response to ongoing public debate. Specifically, the federal government of Canada has delayed the start of its ZEV mandate by one year, pausing the 2026 target of 20 percent ZEV sales and initiating a 60-day review of the policy. This decision was attributed to trade pressures and a desire to reduce the burden on automakers. Meanwhile, the UK government has re-confirmed that from 2030, all new cars must be hybridised or zero-emission, explicitly allowing the sale of full hybrids (HEVs) and Plug-in Hybrids (PHEVs) alongside ZEVs until the 2035 deadline. These two cases highlight the dynamic nature of this transition.

Barbados matches this level of ambition with its 2035 100 percent EV mandate for new passenger vehicles. Rwanda has set one of the highest market-share targets globally, aiming for 70 percent of new vehicle registrations to be electric by 2035. Cuba is aiming for 70 percent of newly registered vehicles across segments to be electric by 2035. Nepal emerges as perhaps the most remarkably ambitious developing economy. Its strategy encompasses nearly the entire transport ecosystem, from private cars and two-wheelers to public transport, freight, and waste collection vehicles. Crucially, Nepal backs its targets with quantified infrastructure projects and conditional financial plans, demonstrating a sophisticated and costed roadmap for implementation.

At the supranational level, the European Union represents the most extensive regulatory framework, with binding legislation for a 100 percent CO₂ reduction for new cars and vans by 2035 and similarly ambitious escalating targets for urban buses and heavy-duty vehicles.

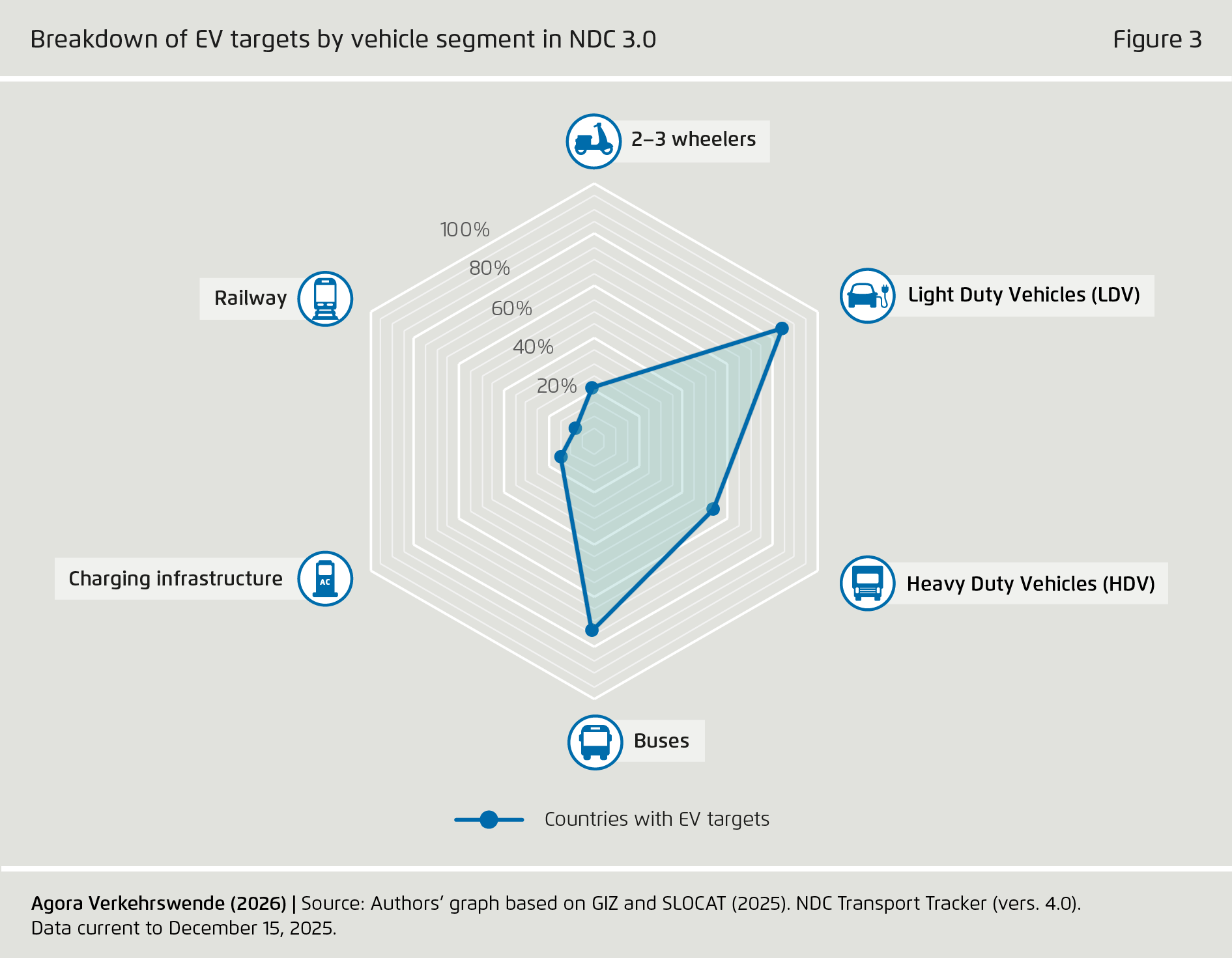

In terms of vehicle segments, light-duty vehicles (LDVs) have a dominant focus among the 66 countries that submitted NDCs 3.0 with e-mobility targets by mid-December (see next figure): 56 countries (85%) have set targets for those, followed by 49 countries with targets for buses (74%), 36 with targets for trucks (55%) and 13 for motorcycles and three-wheelers (20%). Charging infrastructure, which is a critical enabler of EV adoption, is notably absent from most plans. Only nine countries (China, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Liberia, Pakistan, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra Leone, Suriname, and the United Arab Emirates) include specific targets for deploying charging stations.

-

Comparing EV ambition in NDC 2.0 and 3.0

A comparative analysis between NDC rounds reveals a landscape of growing ambition. There is a marked increase in specificity and scope between NDC 2.0 and NDC 3.0, with 52 countries articulating their electric mobility targets for the first time (see next figure). The NDCs of countries like Nepal and Belize have evolved from containing general statements or single-measure approaches to comprehensive, multi-faceted strategies. Nepal, for instance, not only increased its 2035 sales targets for public passenger vehicles from 60 to 90 percent but also introduced new targets for freight vehicles and detailed, costed infrastructure projects. This shift from vague policy intentions to measurable outcomes is a critical step for ensuring accountability and attracting investment.

However, this positive momentum is also accompanied by a countervailing trend of diminished ambition. Nine countries – Andorra, Brunei Darussalam, Cabo Verde, Chile, Honduras, Jordan, Seychelles, Tonga, and Uruguay – had established specific EV targets in their NDC 2.0 that are now omitted from their NDC 3.0 submissions. For example, Chile has removed its previous target of achieving 100 percent electric taxis and public transport, while Uruguay has withdrawn its goal of achieving a 30 percent share of electric vehicles in new car sales by 2030. These commitments had previously sent clear and valuable signals to the market.

The following timetable provides a visual overview of national targets across all parties with EV targets in the new round of NDCs.

Policies supporting EV market uptake

-

Policies supporting EV market uptake

Following the prior section’s assessment of national electric mobility targets, this section analyses the policy measures and implementation pathways outlined in the NDCs to achieve declared ambitions. Put simply, targets define the “what” and “when”, while policies describe the “how”. We classify policy commitments using a three-tiered scale that ranges from highly specific and actionable measures (Tier 1) to generic and aspirational statements (Tier 3). This categorisation reveals clear patterns regarding the global readiness to implement the transition to zero-emission transport technologies. Our policy tiers are as follows:

- Concrete and actionable measures (Tier 1): Robust measures that specify how one aspect of the EV transition will be realised. Such measures include quantifiable, temporally defined actions for implementation, including specific funding amounts, infrastructure numbers, and/or regulatory phases with clear deadlines. Examples include the European Union's binding regulation mandating a 100 percent reduction in CO2 emissions from new cars and vans by 2035, with clear interim targets for 2030 and for HDVs. Similarly, Barbados provides a highly specific policy with its tax holiday for electric vehicles, explicitly "extended for an additional two years until March 2026", and reports exact fleet progress. Other prime examples are Rwanda's target for 70 percent of new vehicle registrations being EVs by 2035 alongside a plan to roll out 2,000 e-motorcycles, and Thailand's quantified investment plan for 80,000 e-trucks and 5,000 e-intercity buses, with associated costs and emission savings. These policies are concrete and amenable to monitoring, hold governments accountable, and provide the clearest signals to the market.

- Implementation-focused measures (Tier 2): This category comprises the majority of NDCs analysed. They describe a clear course of action or enabling condition but lack the specific numerical targets or firm deadlines that define Tier 1. For instance, Angola plans to develop nationwide charging infrastructure and launch pilot projects for electric buses, and Jordan is establishing a fast-charging network with tax incentives. While these pledges demonstrate a clear intent and a defined pathway, the absence of quantifiable outcomes makes it difficult to measure their direct impact and to hold countries to account in terms of implementation speed and scale.

- Generic and aspirational declarations (Tier 3):These are declarations of intent without a concrete plan or measurable outcome. Policies from countries like Botswana (to “provide incentives”) and Brazil (to “replace fossil fuels with electricity”) fall into this category. While they indicate political support for the energy transition, clear adoption targets and metrics for verifying success are missing, thus limiting confidence in meaningful policy execution or outcomes.

Among the 128 countries that submitted NDC 3.0, 104 have some form of EV policy. Within this subset, there is a minority of nations, both developed and developing, such as the European Union, Barbados, Rwanda, and Costa Rica, that are setting the standard with concrete, time-bound, and quantified targets for vehicle adoption, fleet renewal, and fiscal measures. In this way, while most countries present strategic plans that clearly outline “what” needs to be done, such as developing national strategies, launching pilot corridors, and introducing incentives, the majority neglect the question of “how much by when” — a crucial component of actionable policy. This implementation gap is compounded by a critical blind spot: the under-specification of charging infrastructure. With very few exceptions, national vehicle adoption goals are not matched by explicit, quantified, and funded targets for the deployment of public and private charging networks, revealing a potentially critical bottleneck for the envisioned rollout of electric mobility.

Alignment with existing international EV commitments

NDCs are being submitted in a context of existing international commitment within and beyond the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In the following, we assess the ambition of EV targets in NDC 3.0 in relation to Long-Term Strategies (LTS), which provide a mid-century vision, and the 2021 Zero Emission Vehicles (ZEV) Declaration, which sets a clear phase-out date for light-duty ICEV sales.

-

Alignment with Long-Term Strategies (LTS)

Parties to the Paris Agreement are invited to submit Long-term Strategies (LTS), or long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies, to complement the ten-year time horizon of NDCs with a long-term vision. They are a crucial indicator of countries’ commitments to reach net-zero GHG emissions by mid-century and thereby keep the Agreement’s targets within reach.

Of the 84 countries which have submitted LTS (most of them between 2020 and 2024), 29 include specific EV targets. The following table details how EV targets have been carried forward, or, in some cases, omitted, between a country’s LTS and its latest NDC.

With the exception of Armenia, Bosnia Herzegovina, and Equatorial Guinea, all countries with EV targets in their LTS submitted an NDC 3.0 by the end of 2025. Some 80 percent thereof maintained an EV target in their latest NDC, while 20 percent dropped their target. At the same time, the number of countries with EV targets increased by 20 percent between LTS and NDC 3.0 (from 51 to 61 countries).

Overall, policymakers and the broader public are increasingly aware of the important role of electric mobility for climate change mitigation, particularly in the transport sector. While EV adoption has surged in recent years thanks in part to technological improvements and declining costs, further progress in fleet electrification is becoming increasingly salient as the time horizon for action shifts from mid-century (for LTS) to 2035 (for third-round NDCs). With EV markets maturing just as it becomes ever more necessary to end the sale of combustion engine vehicles, the 2030s will be decisive for reaching net zero by mid-century, not least given the 15-year average life span of passenger cars.

-

Alignment with the Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Declaration

The ZEV Declaration, launched at COP26 in 2021, aims for all new car and van sales to be zero emission by 2035 in leading markets and by 2040 globally. At COP21, 31 national governments signed the Declaration, which marks a significant forward step in the effort to phase out the sale of new internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) in the light-duty segment. As of 2025, 44 national governments have adopted the Declaration.

As the Declaration was launched, many countries had either already submitted their NDC 2.0 or only decided to sign up at a later stage. Accordingly, the 17 EU signatories were the only ones to include a ZEV-compatible phase-out target. In this way, the third NDC round can be seen as a litmus test for the implementation of the ZEV Declaration – as the first target year, 2035, coincides with the time horizon of the NDC 3.0.

Among the 21 signatory countries to the ZEV Declaration (plus the 17 EU member states collectively) that have submitted a new NDC, only a few have included a national ICE phase-out target that is aligned with the Declaration's ambition. Specifically, the targets outlined in the NDCs of the European Union, Canada, and the United Kingdom are compatible with the 2035 goal. Other signatories, such as Colombia and Nigeria, have set only partial electrification targets in their NDCs that fall short of a full phase-out. This indicates that for many countries, the ZEV Declaration remains a standalone political commitment that has not yet been operationalised into their formal climate strategy.

It is crucial to recognise that a country’s climate ambition is not defined solely by its NDC or its endorsement of international declarations. Significant policy developments often occur at the national level, through domestic legislation, sectoral strategies, or sub-national regulations, which may not be fully captured in international submissions. For instance, Uganda, an emerging economy which is not a signatory to the ZEV Declaration, has nevertheless established a robust domestic target of 100 percent electric passenger car sales by 2040, as well as targets for bus and two- and three-wheeler electrification as early as 2030. Similarly, in 2024 Ethiopia enacted a more immediate measure, banning the import of internal combustion engine light-duty vehicles. In the absence of domestic vehicle manufacturing, this effectively functions as a 100 percent EV sales mandate. These examples demonstrate that the absence of an explicit commitment in international policy contexts should not be equated with the absence of national action or intent.

Final remarks

-

Final remarks

This analysis of the third generation NDCs provides a global snapshot of political intent for the electric vehicle transition at a critical juncture. Our findings reveal a world standing at the crossroads: while formal ambition is rising, commitments often lack the specificity required to transform pledges into economic reality.

For industry leaders, these findings deliver a clear, if complex, message. On one hand, the upward trajectory in NDC ambition, coupled with the fact that over 62 percent of the global car market is already covered by NDC-based transport electrification or ICE phase-out targets, demonstrate a clear direction of travel for markets and associated regulatory frameworks. The transition to net zero is not a hypothetical future; it is the established policy trajectory of the world’s largest economies and a growing number of emerging markets.

On the other hand, a persistent lack of specificity, particularly with a view to infrastructure, coupled with wavering or withdrawn targets by some nations, is creating uncertainty that can delay investment and slow the pace of change. Industries cannot plan confidently on aspirations alone; they require the clarity of detailed roadmaps, stable regulations, and synchronised infrastructure rollouts.

The path forward will thus involve converting political ambition into market certainty. sound foundation for planning by all market participants. Therefore, the imperative for the next NDC cycle and parallel national policy is clear: countries must rapidly convert strategic ambition into operational certainty. First, countries should bridge the implementation gap. This means upgrading the prevalent Tier 2 policies into Tier 1 action plans by attaching specific, annualised, and funded targets for vehicle sales, public fleet renewal, and the deployment of public and private charging infrastructure. Simultaneously, high-profile political pledges, such as the ZEV Declaration, must be locked into binding NDC commitments to provide the stable, long-term regulatory certainty that industries require to invest at scale.

Second, this planning should be supported by mobilising tailored finance. Ambitious targets in emerging economies will remain aspirational without dedicated capital. This requires designing bankable EV and infrastructure projects that can attract international climate finance and development bank funding. At the same time, wealthier nations should back their domestic strategies with clear public financing mechanisms to de-risk private investment, particularly for grid upgrades and charging access.

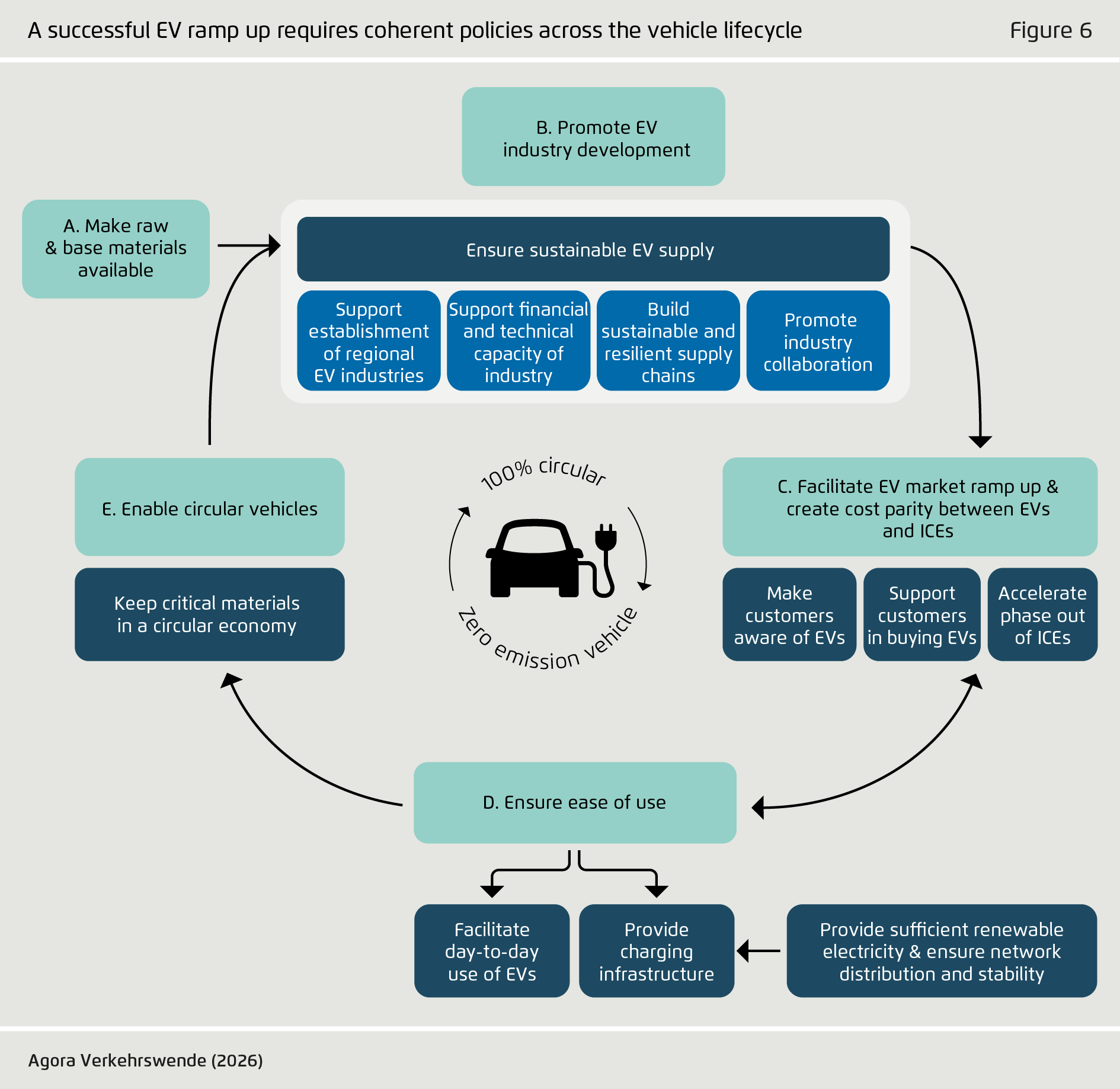

Ultimately, moving beyond isolated vehicle adoption targets is essential. The transition's success hinges on the resilience of the entire industrial ecosystem. This requires governments to conduct structured national assessments and develop integrated plans that address all steps of the EV lifecycle. To support such efforts, Agora Verkehrswende has developed a framework for analysing the comprehensiveness of EV policy instruments (see next figure). This tool is designed to reveal potential blind spots and gaps across the EV ecosystem, thus serving as a starting point for delineating necessary action areas.

The framework covers five critical areas: (A) securing sustainable raw material supply; (B) fostering competitive regional industries and supply chains; (C) creating effective market push-pull dynamics to achieve cost parity; (D) guaranteeing ease of use through robust infrastructure and renewable energy integration; and (E) enabling circularity for vehicles and batteries from the outset. Integrating these areas into national planning can help ensure the EV transition drives not only emissions reductions, but also economic growth, job creation, and energy security.

[1] Based on 2023 market figures for 57 countries obtained from The Global Economy.

[2] Republic of Uganda Sciences, Technology & Innovation Secretariat of the President (2023). National E-Mobility Strategy.